Over the past year, since we, as Warsaw anarchist Black Cross, started publishing our new anti-prison and anti-repression newsletter, we have put lots of attention to torture subject, to those who experience it, and to institutions and states that use it. Our aim is calling for solidarity and opposing such practices. Many of the situations we are describing in our bulletin had place abroad. However, are we aware of what is happening in our backyard? Over the last two to three years, this subject has become more visible in Poland as a result of the increasing number of published and disseminated information, mainly focusing on police violence. Police violence is a fact, an undeniable fact. However, as we will show, unfortunately, this is not the only problem we have to face. The following text aims to bring this problem closer to you and to look at it from a number of perspectives.

Why is there “no torture” in Poland?

The question is, as you certainly noticed, perverse. Is there really no torture in Poland? What about all the cases of beatings and killings committed by the services? What about extortion? In Poland, torture exists in reality, but it does not exist in the sphere of documents and law. To put it simply, there is only one document in this country, namely a paragraph referring to this subject, namely Article 40 of the Constitution: “No one shall be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. The use of corporal punishment is prohibited. However, there is no mention of this in the Criminal Code, the Police Act or any other law. Thus, there is no “state” definition of torture, no definition of what it is, and even less of the consequences for those who use it. Of course, we are not talking about international agreements, human rights charters and so on. We are talking about documents that have force in this country.

Thus, people who have experienced any form of inhumane treatment on the part of the state can only invoke the paragraph on the exceeding of powers. This is not a joke. The Office of the Ombudsman has been informing about this problem for years and has been calling for changes to be made to legislation. The result is, of course, poor, and every year, more and more people experience what we can boldly call torture.

Where is torture used?

Although the most frequently reported cases of inhumane treatment of people relate to the situation in police stations, police cars or simply in the street, these are not the only places. The annual reports of the National Torture Prevention Mechanism (KMPT) show that they are equally used in other institutions: prisons and detention centers, psychiatric hospitals, social welfare homes, sobriety centers, juvenile detention centers, border guard facilities, refugees detention camps, care and treatment centers or 24-hour care centers for the disabled, chronically ill and elderly. The list is long and frightening. The more so because practically each of us, or a person close to us, has stayed in one of these places at least once in his or her life. There are more than 3 000 such institutions of detention in Poland, and in many cases there are drastic abuses.

What happens behind the closed doors?

The word “torture” can be interpreted very broadly so we would like to stress that it does not refer exclusively to the use of physical violence against a person deprived of liberty, but to every act of violating their dignity, intentionally inflicting pain or suffering, both physical and psychological. The KMPT describes many situations that can be treated as torture and inhumane treatment, even though we may not have thought of it every day. Here are some examples observed in Poland.

Prisons and detention centres:

– physical and psychological violence by guards

– concealment of detainees’ injuries

– lack of access to health care – particularly necessary for trans-prisoners or addicted prisoners

– Conducting a personal inspection in breach of the dignity of the detainee, e.g. when an officer does so, laughing at prisoner or inspecting in a place that does not ensure isolation from third parties, in the event of sexual harassment during an inspection, etc.

The detention of detainees in cells of more than a dozen persons is an important problem and little thought is given to it. According to the Bureau of Information and Statistics of the Central Board of the Prison Service, until 31 July 2018 there were 89 cells in polish prisons with more than ten prisoner’s bed: 13 cells for 11 people, 23 cells for 12 people, 18 cells for 13 people, 6 cells for 14 people, 2 cells for 15 people, 23 cells for 16 people, 3 cells for 17 people and one cell with 18 people. Placing many prisoners, who often have problems with controlling emotions, in this kind of conditions causes an increase in tension and stress, which in turn leads to conflict situations. Not without significance is also the very low level of activity outside the cell of such people in prisons of the closed type. Each conflict is a threat to the personal security of the detainee. The main victims are the weaker prisoners who, for various reasons, occupy a lower position in the group.

Living conditions there are also difficult. They are often equipped with only one toilet and one washbasin, which violates the right to privacy of prisoners. Lack of efficient ventilation causes the cell to be stuffy and the unpleasant smell from the sanitary corner is constantly maintained.

– violation of the right to communicate with the outside world (including a lawyer and family) and of the right to information (e.g. about the rights of the detained person)

– the insufficient number of psychologists – in prisons and detention centres there is 1 psychologist per 200 detainees!

Juvenile detention centres:

– police officers prevent a detainee from having private conversations with his or her family or with a lawyer

– no legislation on personal inspections (!) – searches and personal inspections are carried out by persons without appropriate powers

– Physical and psychological violence in youth education centres is experienced by every 4 prisoners.

– forcing prisoners to carry out manual labour, even without adequate training

– no access to a lawyer immediately after arrest

Psychiatric hospitals:

– “Accommodation’ of people in the corridor

– lack of regulation in the area of monitoring

– the systematic application of direct coercive measures

Refugees Detention Centers:

– lack of identification system for victims of torture – according to international regulations, persons who have experienced torture/ inhuman treatment/life threatening and resulting trauma should not be placed in guarded centres for migrants at all.

– detention of children and young people

– use of direct coercive measures (let us remind you that refugee centres are not prisons in theory, are they?)

– no possibility to communicate with the outside world

– lack of access to information about their legal status, rights, aid institutions, etc.

– lack of psychological assistance and absolutely insufficient access to other medical care

– officers always wear visible tasers, guns and truncheons – this behaviour increases the sense of danger for the detainees, increases trauma or, in the event of violence by the officers, creates new ones.

The examples given above are not the experiences of a small group of detainees, nor of those “most dangerous” or “most difficult”. They are not only the experiences of those involved in political activities. Every day, thousands of people with different positions, backgrounds, sensitivities and resilience have to face abuse. These are not just blank points, abstract examples. Each year the KMPT report describes individual stories of people who have experienced violence in different penitentiary institutions.

“I was beaten during interrogations. They beat me all over my body with a baton in my heels. They threatened to find me and my family. They wanted me to confess to the burglaries of the allotments. During the interrogations, I was handcuffed all the time. It lasted a long time. I didn’t get anything to eat or drink. I could only drink water when they finally let me use the toilet. They questioned me several times. I was beaten every time. I finally confessed, but only because I wanted them to leave me alone.”

“I found myself in a solitary cell because I beat up another prisoner. I did it because I wanted to be alone for a while. I don’t even have a minimum of privacy in the cell where I’m serving my sentence.”

“The teacher pulled the pupil out of the bed and hit him in the face (the reason was to draw the teacher’s attention to inappropriate behaviour during the night), pulled him apart; hit him on the face (for refusal to perform duties); twisted his hands and hit his neck, hit his belly; used words commonly considered offensive (“shut up”, “the faggot made you”)”.

“The detained person was forced to move around the unit with his trousers down to his knees and intimate areas exposed.”

“During the inspection of the social welfare home in Elk City, the monitoring analysis from the isolation room showed that the nurses do not know the rules of coercion, use the help of another resident for immobilization and do not control the condition of the immobilized resident.”

Why do we allow this to happen – why is it happening?

Social acquiescence

Is torture socially acceptable? As a member of the anti-prison and anti-repression movement, I would like to believe that it is not. The very sound of this word causes me a strong emotional reaction, which is reflected in the body – I feel the tension in the muscles around the abdomen and automatically pull my arms to the chest. The body reacts as if I wanted to protect myself from danger. I have experienced police violence in the past, but none of these cases would qualify as torture. However, I know the stories of people – close or distant, but part of the anarchist movement, from Poland and other countries that have just experienced it. And each of these stories aroused my enormous anger and disagreement, the need to fight against such methods. I would like to believe that my reaction is universal… that resistance is a natural reaction to such practices. Unfortunately, I am aware that this is only my naive wish.

In 2018, the Ombudsman’s office published the results of a report carried out by Kantar Millward Brown, according to which 41% of a representative group of polish people between the ages of 18 and 75 allow torture. The vast majority agreed that the following can be qualified as a form of torture: extraction of testimony using physical and mental violence, use of violence as a form of punishment, degrading treatment and “unjustified” use of force. As circumstances allowing for the use of such methods, these persons indicated: the need to extract information (90% of persons allowing torture), break resistance tests (88%), deterrence from committing crimes (85%) and the need to punish the offender (87%).

Of course, one can look at these statistics with a “more optimistic” eye, noting that at the same time 59% of the respondents are opponents of torture. These people explain their opinion as follows: torture violates fundamental human rights (94% of people who do not allow torture), harming a defenceless person is morally unacceptable (93%), is associated with the past and should not be present in the modern world (93%), consent to torture has a negative impact on the state legal system (94%), is inconsistent with international treaties (93%), their use is contrary to religious values (91%), does not help to obtain important information and does not prevent crime (86%).

These statistics are puzzling for me as in the same survey as many as 71% of all respondents believe that torture is used in Poland, and their most frequent perpetrators are the police (87% of respondents) and the prison service (45%). It appears that a really large part of our society knows about the use of torture, has probably experienced or knows other people who have experienced violence from state institutions, and at the same time still believes that in some cases it is acceptable. What is more, it accepts torture as a form of punishment, even though the “official” tool adopted to punish people in this country is forced isolation. For some, for me as much as for others, it is forced isolation. From this examination, I draw the additional conclusion that the fight to end torture is all the more difficult the more abuses by the authorities and their institutions can be calmly accepted and accepted by society.

Institutional acquiescence

At the end of 2018, I watched a panel on the use of torture in Poland, which was organized as part of the Second Civil Rights Congress – an initiative of the Ombudsman’s office. During the panel, people connected with the KMPT spoke, among the others. I think that it is worth referring to this event in this text because the topics discussed in it help to understand how institutional consent to torture by public functionaries is built.

However, I will start with something else, namely the sense of absolute impunity of the police and the consequences of this fact. In 2015, the Ministry of the Interior asked an external company to conduct a survey among police officers on the scale of aggression in the whole formation. The results of the survey are not surprising for me personally, and much is said about them by the fact that such a survey has not been repeated since 2015. A comprehensive report (over 250 pages) I recommend what to persistent readers, while here I will quote only a part of the information contained in it.

Let us start with the fact that about 45% of the surveyed functionaries admitted that they once participated in a situation in which “the actions of a policeman could be perceived by a person outside the police as excessively aggressive”. Beautiful euphemism. Going further – about 13% confirm that such situations constituted at least 1/5 of the last 100 official actions, and for 3.50% it was even up to half of the last 100 actions taken.

What aggressive behaviour do they notice in themselves or have they witnessed? 73% indicated the use of incapacitating grips, 68% use of physical force, 43% coercion of an inconvenient position, 42% indicated insulting statements, 29% indicated humiliating statements, 25% indicated hand beating or kicking, 17% indicated hitting with an object other than a professional baton, 16% indicated illegal use of handcuffs and 16% misuse of the baton itself.

Not a bad result for an institution which, according to the December national statistics agency survey, is said to enjoy the greatest social trust – higher than 90% (sic!).

And what is the situation like in the case of people who experience police violence? Not better at all. Here I can refer to two sources. In May 2016, the journalist from one of the biggest mainstream newspaper in Poland wrote that the main police headquarters provided her with data showing that in the years 2011-2015, approximately 16,000 complaints against uniformed officers have received annually, out of which only about 1,300 were considered confirmed. The Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights published its data, indicating that in 2016, 538 complaints were filed against the inhuman or degrading treatment of the police, 387 of which were transferred to court. In the same year, 6 final sentences were passed.

What picture does this give us?

Police violence + no consequences = institutional consent

Looking at torture from an institutional and democratic perspective

Perhaps the good news is that someone in this country is interested in the problem of torture, and more or less effectively is trying to combat it. What is more, there are people in state structures who say loudly that torture is being used and must be eradicated. The question is, how? This is what the panel on ‘Poland as a country free from torture’, which I mentioned earlier, was devoted to. Despite the fact that I personally disagree with some of the arguments put forward in it, and even with some of them very much, I decided to write down some of them:

Preventive instruments against torture

According to the panellists, several such “fuses” can be distinguished to guarantee the safety of detainees and detainees in different detention centres:

– visits of detention centres by independent institutions

– civil monitoring

– introduction of a legal basis – reducing impunity for torture

– a guarantee of knowledge and the possibility to exercise the rights of a person deprived of his or her liberty, in particular:

– the right to contact with family and lawyer immediately after the arrest – most cases of abuse of rights by officers/officer take place on the first day after the arrest),

– medical examination and keeping meticulous records – there are recorded cases in which in the medical records of the detained person the doctor does not mention any traces of violence, which he/she has experienced

– judicial supervision

– video-monitoring – in the uniform and in the rooms where the detained person is staying

– an effective complaints mechanism

Conditions to be met for preventive mechanisms to work

– development of democracy – one of the panellists, mr Zbigniew Lasocik, argued that there is a correlation between the existence of the regime and torture (oh, really?)

– political respect for human rights and international agreements (where? Here? c’mmon.. )

– economic growth – the thesis that there is less tolerance for torture in developed countries (seriously?)

– no conflicts or tensions on ethnic or religious grounds

– membership of international organisations

– Criminalization and prosecution in case of torture.

The problems we face

lack of control mechanisms – the body, which is the National Torture Prevention Mechanism, is exclusively monitoring and giving recommendations to improve the conditions of persons deprived of their liberty. However, there is no mechanism to monitor whether these recommendations are being implemented. Without this mechanism, every KMPT report is treated only as a collection of “good advice” to which the services and institutions of detention may or may not refer;

Inability and unwillingness to use the tools developed to help prevent torture. An example of this is the so-called “Istanbul Protocol”, which can be explained as a kind of checklist for doctors. This protocol allows for a step-by-step check of the health of the person under examination to determine whether they have experienced torture. The problem is that it is not used by any service, centre or court. This is explained by the lack of knowledge of how to analyse such a document;

lack of education in the field of torture prevention

Proposed measures to improve the situation

amending the law to include a provision on the prohibition of torture in the Penal Code and the consequences of its violation

publishing international reports

educational activities: among officers, victims, prisoners, society

Looking at torture from an anarchist perspective

During the panel, mr Lasocik was tempted to make a statement..: “People torture not because they are bad, but because they are inspired to do so in different ways”. Shortly afterwards, he added a metaphor for the black sheep that I could not understand, explaining that our goal should be to stop certain behaviours but not to demonise the entire police institution. This awakened my vigilance and resistance. If I keep to this unfortunate metaphor, I would rather say that this is not just one black sheep, but a whole herd of black sheep that is the service. All the services.

I am not going to go into a deep analysis of what good and what evil is. All the more reason I would not dare to morally judge which man is good and which is bad. However, I do not agree with such a clear example of whitewashing the faces of uniformed organisations and taking away their representatives and representatives of subjectivity, and consequently – suffering the consequences of their actions. I do not imagine that I should say “He is a bad man because he tortures”. The same bizarre sentence would sound to me like “He’s a good husband and father, only at work he sometimes tortures people”. Why is it so bizarre for me? Because in my opinion, this opposition between good and evil does not matter that much. I put much more emphasis on something else. I do not agree with torture, because I do not agree with limiting the freedom of others. I do not accept torture, because my body and mind belong to me and are far from them. I do not accept torture, because it is the sole tool of the state to maintain control and fear. It has nothing to do with good or evil.

Torture is carried out by specific people working in specific institutions. It is therefore impossible to separate one from the other – to point the finger at people without referring to institutions, or to criticize institutions without mentioning the people who work in them. And yet the problems are super visible in both. The services (police, prisons, border guards, etc.) are more and more random, untrained, susceptible to influence. After several years of work, solid brainwashing, absorption of the culture of power and domination, and several lessons of impunity, they become well-functioning cogs in the apparatus of repression. And of course, as I have already mentioned, violence and torture are systemic problems. However, this does not justify the use of violence by individuals, does not give them the mandate to abuse their powers, does not give them the right to sweep the problem under the carpet. In order to eliminate torture, therefore, it is not enough to reform individual cogs; the entire institution should be reformed. Is this possible? In my opinion, it is not.

The police, the prison service, the border guards, the courts, etc., are all political institutions. Many people could now raise their voices against it. But that is the way it is, and I am not saying that politically they serve one particular party. No. Politically, they serve to maintain control by any authority that is just about to get to power. So the institutions cannot be reformed within the current order if that would jeopardise the existence of that order. There is a need for a complete change, for alternatives based not on force and violence, but on social equality and solidarity. Does it sound utopian? Very well, let us be utopian, but let them keep their hands off us, our body, our mind and our freedom.

I think much more pleasingly of this utopia than of the obvious dissonance between the “mechanisms for the prevention of torture” proposed by the institutions and the real experiences of anarchists and migrants. How many of us have seen sparks of joy in the eyes of a policeman who has just come to beat you up on a blockade? How many of us were beaten up in police cars? How many of us have experienced sexual violence at police stations? How often do they deny us the right to contact the lawyer, even if we know that we have the right to do so? And are we still surprised when we read about another hunger strike by our anarchist friends behind the walls? The fact that they are more likely to face consequences, punishments, beatings, restricted visits, failure to deliver parcels is not a coincidence. It is an attempt at pacification that no preventive mechanism can stop. Of course, when we are experiencing repression from the state, we want to defend ourselves, and it is also justified to use institutional tools, such as access to a lawyer, an attempt to shorten the sentence, appeals, etc., in order to protect ourselves. I understand those who, because of their views, completely renounce these measures, but at the same time I am far from criticising those who benefit from them. However, we must remember that we cannot actually rely on them 100%. Their effectiveness depends on what we see now, and we succeed and fail.

Apart from attempts at pacification by all forms of violence, torture can also have a different purpose. The services are trying to gather information in that way – and not only about what a person has done or has not done, but about what s/he could do, with whom work with, who is holding onto whom, who is worth hitting now. Torture is to break, to force to cooperate, cut off from the environment with which the person identifies himself or herself. Is there anything even more dangerous? Torture is a tool for forcing people to confess to a crime, even if they have not committed it, or a tool for breaking solidarity and giving up our friends. In the last year, the anarchist movement in Russia has been the hardest hit, but this is neither the first nor the only, and probably not the last case.

The strategy used in Russia to create a completely false story and force the defendants to confirm it is the worst-case scenario. However, it has become our reality, to which we must respond. We need to be quick and effective in order to stop this trend before it becomes massively exploited by more countries. Our actions must be comprehensive if they are to be effective. It is not just about to stop police beating people, or the prison service not taking advantage of convicts, or the border guards stop abusing migrants. It is about building a society that does not need any police, prisons and borders. A society – not just a movement – based on solidarity, equality, freedom and a sense of security.

Radio Blackout – Torino

Radio Blackout – Torino Radio Bronka – Barcelona

Radio Bronka – Barcelona Radio Klaxon – ZAD Notre Dame de Landes

Radio Klaxon – ZAD Notre Dame de Landes Police Spies Out of Lives

Police Spies Out of Lives Contrainformación Anarquista

Contrainformación Anarquista Luca Zanette

Luca Zanette The anarchist library

The anarchist library Khimki Forest

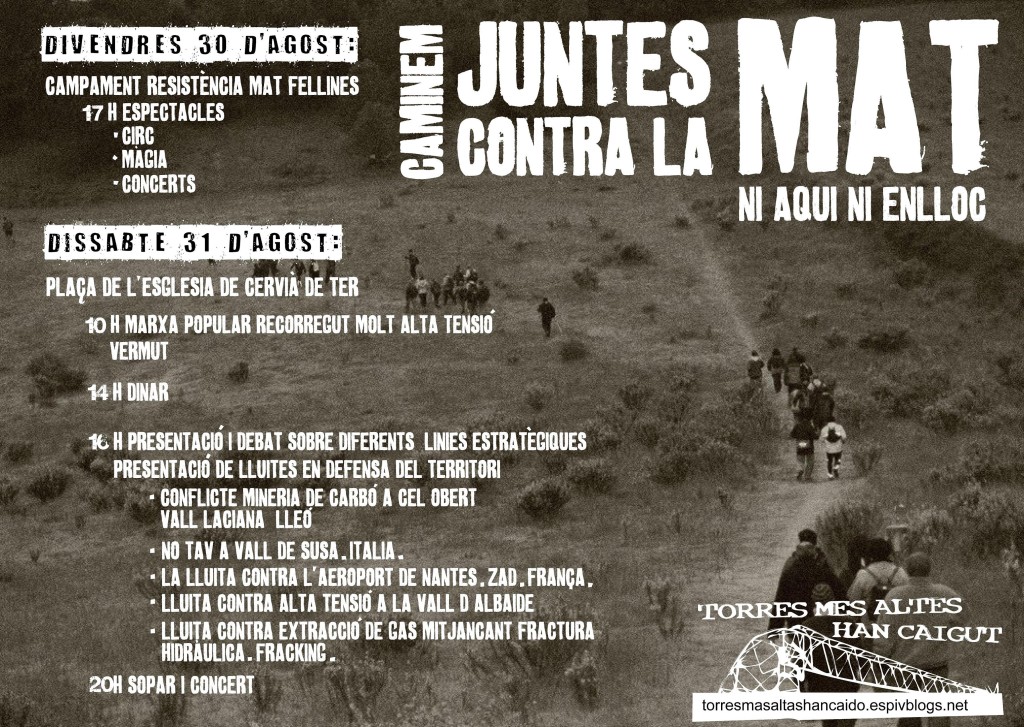

Khimki Forest No Mat Catalunya – Campada

No Mat Catalunya – Campada No THT France

No THT France NoTav

NoTav ZAD – NotreDame de Landes

ZAD – NotreDame de Landes Usurpa!

Usurpa!