President Erdogan has declared a three month state of emergency which allows the government to bypass parliament and rule by decree. Tom Stevenson writes from Istanbul that this has triggered support but also concern.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared the three month state of emergency on Wednesday after a gruelling four and a half hour meeting of the National Security Council.

Since the coup attempt on July 15, authorities have engaged in a post-coup crackdown that has seen more than 8000 detentions across the country and mass suspensions in public institutions.

Curfews, restrictions on free assembly, the power to restrict the publication of books and magazines, these are just some of powers the Turkish government has granted itself in recent days.

Turkey’s civilian government may have narrowly avoided a coup, but now it has reinstituted a state of emergency written into law in 1983 by Turkey’s old military rulers.

Following the defeated the coup attempt, the government has been enjoying widespread public support – but the declaration of a state of emergency also leaves many uncomfortable.

“Of course after this coup the government had to do something,” said Gurkan Aydemir, the owner of a cafe in Istanbul’s Beyoglu district. “But I am very worried that after all this they will just go too far and go crazy, I’m very worried about that.”

The state of emergency allows the government to bypass parliament and rule by decree, a measure that has some in Turkey worried that the ruling AK party will use the post-coup moment to cement its own authority over the political opposition.

Officials say the state of emergency is modelled on states of emergency after terror attacks in France and Belgium and is intended to put every tool at the disposal of the authorities to secure the country.

Deputy prime minister Mehmet Simsek, who is seen as a moderate in the Turkish cabinet, sought to reassure the public that the state of emergency would not greatly impact their lives.

“This measure is aimed at holding coup-plotters accountable and ensuring those involved are identified and brought to justice swiftly,” he said. “Life of ordinary people and businesses will go un-impacted, uninterrupted, business will be as usual.”

In the aftermath of the coup attempt president Erdogan has publicly raised the idea of reinstating the death penalty, which was abolished by Turkey during the EU accession process in 2004.

A state of emergency, which can be renewed after three months, has not been declared in western Turkey for many years.

“It’s actually a relic of military dictatorship in the 1980s,” said Andrew Gardner, Amnesty International’s researcher in Turkey. Gardner pointed out that basic rights and freedoms are protected by article 15 of Turkey’s constitution even under a state of emergency, however he says there’s no guarantee the authorities will abide by the letter of the law.

“We’re very concerned that this clears the way to a more restrictive path for the authorities who have already frankly behaved in a way that has disregarded the rule of law.”

The post-coup crackdown has already seen 15,000 workers at the education ministry, more than 2500 judges, and hundreds of civil servants suspended from duty pending investigations into the coup plot. Following a government request, the dean of every university in the country has temporarily resigned.

“There was a horrific, violent coup attempt, and swift action was needed, but with the risk of military rule averted, unfortunately the Turkish government appears to have reacted in a manner that is reminiscent of previous military rule in Turkey,” Amnesty’s Gardner said.

“The direction that Turkey is heading in, not just with failed coup attempt, but the crackdown that has followed it, is certainly not good and the decisions taken in these few days may create problems that will be felt for a much longer time ahead.”

Radio Blackout – Torino

Radio Blackout – Torino Radio Bronka – Barcelona

Radio Bronka – Barcelona Radio Klaxon – ZAD Notre Dame de Landes

Radio Klaxon – ZAD Notre Dame de Landes Police Spies Out of Lives

Police Spies Out of Lives Contrainformación Anarquista

Contrainformación Anarquista Luca Zanette

Luca Zanette The anarchist library

The anarchist library Khimki Forest

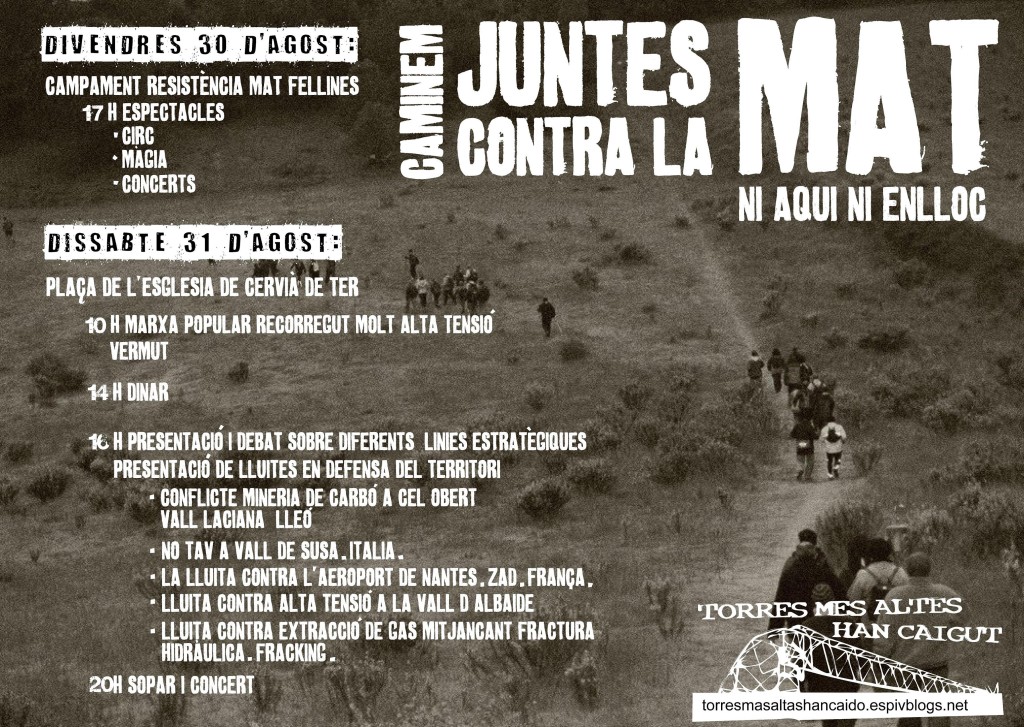

Khimki Forest No Mat Catalunya – Campada

No Mat Catalunya – Campada No THT France

No THT France NoTav

NoTav ZAD – NotreDame de Landes

ZAD – NotreDame de Landes Usurpa!

Usurpa!