The Autonomous Social Centre Klinika, which occupies the building of a former clinic in Prague, has attracted a large number of supporters and was even awarded a prestigious prize. Yet its future remains uncertain.

Since 1987, the Charter 77 Foundation has annually awarded the František Kriegl Prize in the Czech Republic. The award is a reminder of the brave attitude of the Czechoslovak politician František Kriegl, who refused, as the only member of the political elite at the time, to sign the “Moscow Protocol” after the country was invaded by the armies of the Warsaw Pact in 1968 and so legitimate the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Soviet tanks. The current mission of the prize is to highlight exemplary courage expressed by individuals or civic institutions in the quest for upholding human and civil rights, and political tolerance. Its results are announced each year on 10 April, the day of František Kriegl’s birth. This year, the prize was awarded to the collective of the Autonomous Social Centre Klinika, located in Prague’s Žižkov district. Its activists now stand alongside figures such as the Czech dissident Jaroslav Šabata, leading Roma scholar Milena Hübschmannová, or anarchist Jakub Polák, who all held the award previously. It is undoubtedly one of the most telling proofs of the social necessity and importance of the Autonomous Social Centre. “Klinika lives, the struggle continues”, runs the slogan of the movement that arose around Klinika in the past year. But despite the award and the strong imprint that Klinika has left, the centre’s future, symbolically and physically connected with the building of a former healthcare facility in Prague’s Žižkov, is still not certain.

Since 1987, the Charter 77 Foundation has annually awarded the František Kriegl Prize in the Czech Republic. The award is a reminder of the brave attitude of the Czechoslovak politician František Kriegl, who refused, as the only member of the political elite at the time, to sign the “Moscow Protocol” after the country was invaded by the armies of the Warsaw Pact in 1968 and so legitimate the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Soviet tanks. The current mission of the prize is to highlight exemplary courage expressed by individuals or civic institutions in the quest for upholding human and civil rights, and political tolerance. Its results are announced each year on 10 April, the day of František Kriegl’s birth. This year, the prize was awarded to the collective of the Autonomous Social Centre Klinika, located in Prague’s Žižkov district. Its activists now stand alongside figures such as the Czech dissident Jaroslav Šabata, leading Roma scholar Milena Hübschmannová, or anarchist Jakub Polák, who all held the award previously. It is undoubtedly one of the most telling proofs of the social necessity and importance of the Autonomous Social Centre. “Klinika lives, the struggle continues”, runs the slogan of the movement that arose around Klinika in the past year. But despite the award and the strong imprint that Klinika has left, the centre’s future, symbolically and physically connected with the building of a former healthcare facility in Prague’s Žižkov, is still not certain.

What was previously a ruin full of excrement and syringes became a lively space, which began to offer a daily programme – from poetry readings to lectures and concerts and film screenings.

At the end of November 2014, a group of activists managed to occupy the building of a former lung clinic in Žižkov. The former working-class area thus became host to an autonomous social centre linked to the Czech anarchist movement. A number of similar centres had already existed in Prague, and the arrival of the squatters in Žižkov also symbolically built on the activities of Žižkov’s anarchists at the beginning of the twentieth century. At that time, the Black Hand Collective occupied empty flats and handed them over to workers’ families. In the post-1989 era, the most famous Czech squat was probably Ladronka, which existed in Břevnov park in Prague for seven years. The squatters’ eviction on 9 November 1999 basically ended the “golden 1990s” era of the Prague subcultural scene. The Autonomous Social Centre Klinika (meaning “clinic” in Czech) brought a change to the Czech squatting movement. The times of the open-minded cultural centres of the 1990s, whose existence was often justified only by the ethos of rave culture and a fight for the “right to party”, are long gone. As a result, the scene has become much more politicized.

The relationship of the Czech political scene to squatting has been marked mainly by harsh repressive measures and unscrupulous police behaviour in the past decade. The conviction that the inviolability of private property is the main pillar (or practically the synonym) of a free society has certainly also played a role. Even the longest-standing squat Milada near to the university dormitories in Trója could last for more than eleven years only because of an administrative glitch, according to which the building did not actually legally exist. Activists managed to occupy several other buildings, though the occupation of only one of them – the Cibulka “chateau” – survived more than several days thanks to thorough negotiations with the owner. But even Cibulka has now been empty for a year.

At the end of the summer of 2013, a one-day event bearing the name Memories of the Future took place in Prague, in which a number of autonomous collectives took part, including the one that today forms the core of Klinika. Eight derelict buildings were symbolically occupied for a day and hosted a varied cultural programme. The activists thus drew attention to the fact that there are a number of valuable buildings in lucrative locations in the centre of one of Europe’s richest cities, which their owners are deliberately letting fall into disrepair to justify their demolition that would allow for commercial buildings to be built in their place. The happening was aimed mainly at the problem of real estate speculation, which Prague has been suffering from for a number of years.

OBSAĎ A ŽIJ! – documentary film about the event VZPOMÍNKY NA BUDOUCNOST (Memories of the Future) from A2_LARM on Vimeo.

Activists built their argument on a passage from the constitution, which states that “ownership is binding” and it is not possible to leave buildings – which are often protected properties with historical heritage – to their fate. An important underlying theme of the event was also the increase in homelessness. The discrepancy between the number of empty buildings and homeless people, who could find at least temporary refuge in these properties, became a catchy topic taken up by mainstream Czech media. The reputation of squatters as “dirty junkies and slackers, who will pile into people’s living rooms as soon as they go off on holiday” slowly began to change.

The occupation of Klinika in November 2014 brought another new twist. The occupied property belongs to the state, which has weakened the position of the private ownership argument. The derelict building of the former healthcare facility in Jeseniova street has been in the care of the Office for Government Representation in Property Affairs and the house has stood empty since 2009. In fact, the occupying anarchists came dangerously close to the opinions of some libertarians, who see the state as an obstructive instrument of bureaucracy unable to effectively deal with property. Maybe that is also why the topic resonated with Czech society with unprecedented intensity. Significant figures of Czech cultural life came out in support of the Klinika collective in its first days – for instance Vratislav Brabenec from the legendary underground band Plastic People of the Universe, or film director Petr Zelenka.

In the first ten days during which the house was illegally occupied, it underwent a visible transformation. The activists paid for waste containers and joined forces to clear up the property. What was previously a ruin full of excrement and syringes became a lively space, which began to offer a daily programme – from poetry readings to lectures and concerts and film screenings. Even local residents stood at the centre of things and for the first time in a long while, practically anybody could come to experience for themselves what the abstract ideals of the squatting movement actually stood for.

This change of tactics, together with a change of rhetoric, bore its fruits. After an initial eviction of the activists, the first demonstration in support of Klinika attracted more than 1000 people. The local administration of Prague 3, where Klinika is located, and in particular the current leader of the Czech Green Party, Matěj Stropnický, took part in negotiations about the future use of the property. Already his previous activities indicated that Stropnický intended to fight against the influence of power groups – in particular developers – in his district and so enable residents to take part in the decision-making processes about their immediate environment. It is also thanks to Stropnický that the activists could, after a month’s negotiations, begin to run the Social Centre. Prague 3 even concluded a year-long contract with the activists, temporarily legalizing the squatters’ occupation of the former clinic.

From its inception, Klinika worked as an open, participatory and inclusive project. Hundreds, even thousands of people became involved in it. In order to challenge market “logic”, the services and activities offered by the Centre, as well as any refurbishments and alterations to the property, were carried out for free on a voluntary basis. After a series of public voluntary work shifts and fundraisers, which provided both necessary funds to carry out repairs as well as a willing workforce, the collective launched a regular programme with daily additions. Klinika introduced the project of a “street” university, which was joined by many Czech academics. The Centre held Czech language courses for foreigners, ran a furniture repair workshop, opened a public library, and offered facilities to people without a home. The Centre also made its premises available to other collectives, which widened the portfolio of activities on offer to include a freeshop, the children’s centre MamaTata, or a social laundrette.

The collective operated in this way more or less without any problems until August last year, when a humanitarian crisis unravelled in the Balkans and Hungary as a result of the migration of refugees from war-torn countries. Back then, activists from Klinika organized a collection to help the refugees. An initially innocuous status on Facebook soon turned into a country-wide humanitarian initiative. The building literally overflowed with things that took several weeks to be sorted, with the gathered donations being constantly shipped to refugee camps in Hungary and Serbia, as well as to Czech detention centres. It was the initiative of the Autonomous Centre that kicked off the spontaneous wave of Czech aid to refugees.

But the more serious the situation around the refugee crisis became, the more Czech society witnessed an increase in xenophobic and Islamophobic tendencies and Klinika came to the attention of the radical right. Threats and intimidation of the collective occurred on a daily basis and the whole situation escalated on the first weekend in February this year. A manifestation of the German organization Pegida and its Czech equivalent, We Don’t Want Islam in the Czech Republic – which is now preparing for local elections in the autumn – took place in the square in front of Prague Castle. A group of football hooligans attacked the march of the initiative No to Racism and probably the same attackers threw stones and flammables at Klinika’s building a few hours later. There were about 20 people in the building at the time. Fortunately, only one of them was lightly injured.

Paradoxically, the Klinika collective – the victims of the arson attack – have been cast as the perpetrators of the situation as Prague’s right-wing parties competed to see who could gain most political leverage from this violent incident. The mayor of Prague 3, Vladislava Hujová from the liberal-conservative party TOP 09, and other members of the local council, labelled the activists an unprecedented security threat to local residents. They basically drew an equation sign between the Klinika collective and neo-Nazis and began to advocate ending the whole project. It should also be noted that to this day, none of the attackers have been apprehended or charged.

During the first year of its existence, Klinika has become a symbol of resistance against the increasingly conservative and authoritarian tendencies in Czech society.

The following bureaucratic struggle to push out the activists from the building of the former clinic resembled the literary work of two natives of Prague – Kafka and Hašek. The Prague 3 council for instance argued that it cannot prolong Klinika’s contract, because the premises had been approved to function as a healthcare facility and could not be used for any other purposes. Matěj Stropnický’s investigations however showed that thanks to the decision of a certain Communist Party official in the 1960s, the building never received a certificate of occupancy.

During the undignified negotiations of the local council about the future fate of Klinika, Lýdie Říhová from the Christian-conservative party KDU-ČSL declared that the council is currently deciding whether Prague will become more like Berlin or Moscow. Her appeal was not heard by the majority of councillors, who sided rather with the latter option. But the struggle continues.

During the first year of its existence, Klinika has become a symbol of resistance against the increasingly conservative and authoritarian tendencies in Czech society. These also form the background to the strong political pressure and endless search for complicated ways in which to get rid of the Social Centre. If one empty building could shake the ground under the feet of Czech politicians, it is not hard to imagine what kind of earthquake the fulfilment of the slogan “Each city needs its own Clinic” would cause. A large number of Czech politicians have generated enormous efforts in order to make sure that a group of young idealists helping refugees and constantly repeating the idea that “another world is possible” will not be able to remain in a house that no institution of private owner wants. But Klinika has gathered enough determined people, who now possess the political power to show that the building itself is not really as important as letting politicians noisily know that their ideas will not easily be evicted.

Radio Blackout – Torino

Radio Blackout – Torino Radio Bronka – Barcelona

Radio Bronka – Barcelona Radio Klaxon – ZAD Notre Dame de Landes

Radio Klaxon – ZAD Notre Dame de Landes Police Spies Out of Lives

Police Spies Out of Lives Contrainformación Anarquista

Contrainformación Anarquista Luca Zanette

Luca Zanette The anarchist library

The anarchist library Khimki Forest

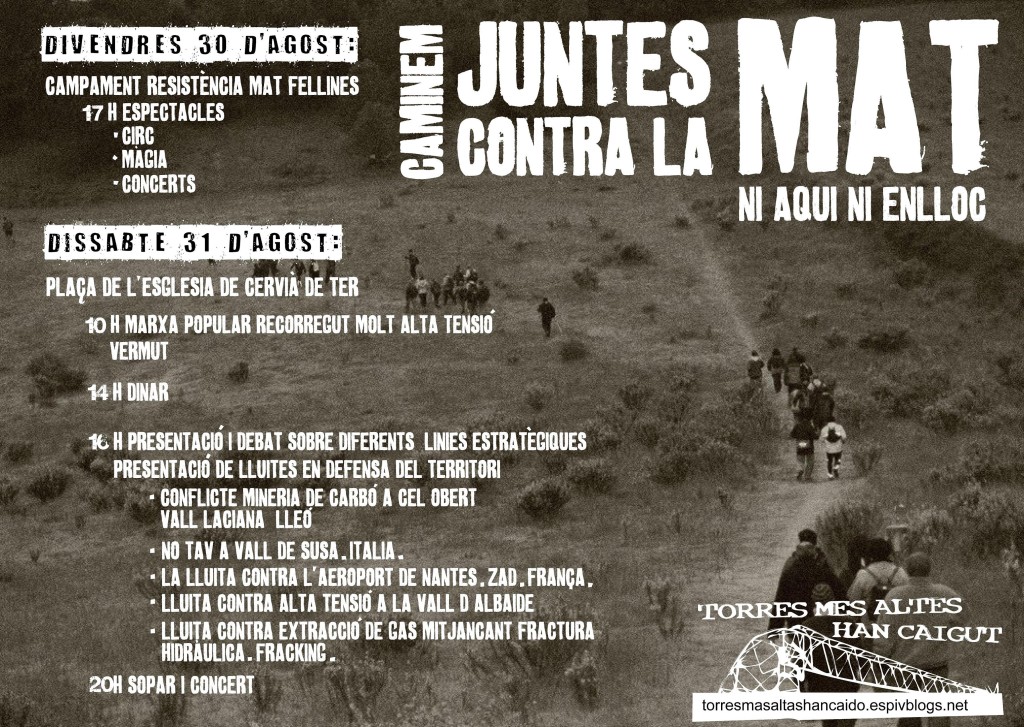

Khimki Forest No Mat Catalunya – Campada

No Mat Catalunya – Campada No THT France

No THT France NoTav

NoTav ZAD – NotreDame de Landes

ZAD – NotreDame de Landes Usurpa!

Usurpa!